| German Revolution | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Postwar revolutionary wave | |||||||

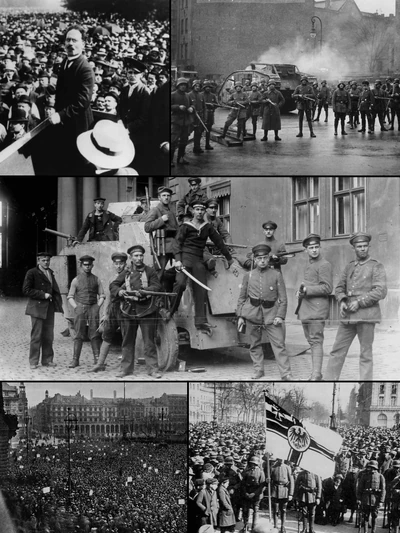

Top left: Karl Liebknecht speaks to a revolutionary crowd in Berlin, December 1918 • Top right: Weimar government troops advance into the outskirts of Berlin, May 1920 • Middle: Spartacist soldiers stand triumphant after the Kiel Operation, February 1920 • Bottom left: Thousands of revolutionary strikers demonstrate in Hamburg as part of the May Revolution, May 1919 • Bottom right: Freikorps troops fly the war flag of the German Empire in Elberfeld (now Wuppertal), March 1920 |

|||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 350,000 killed or missing 900,000 wounded or sick | 240,000 killed or missing 750,000 wounded or sick 100,000 captured |

||||||

1.5–2 million refugees flee from the Spartacists |

|||||||

| |||||

The German Revolution (German: Deutsche Revolution 1918) or the November Revolution (German: Novemberrevolution) was a conflict in the German Empire and the Weimar Republic at the end of the Great War that resulted in the replacement of the German monarchy with a socialist republic. The initial revolutionary period lasted from October 1918 to May 1919 when the conflict escalated to the German Civil War (German: Deutscher Bürgerkrieg) or the May Revolution (German: Mai-Revolution). The civil war period lasted until November 1920, ending with the Treaty of Aachen and the defeat of counter-revolutionary forces.

The causes of the revolution were the extreme burdens suffered by the population during the four years of war, the strong impact of the defeat on the German Empire and the social tensions between the general population and the elite of aristocrats and bourgeoisie who held power and had just lost the war. The first acts of revolution were triggered by the policies of the German Supreme Army Command and its lack of coordination with the Naval Command. In the face of defeat, the Naval Command insisted on trying to precipitate a climactic battle with the British Royal Navy by means of its naval order of 24 October 1918. The battle never took place. Instead of obeying their orders to begin preparations to fight the British, German sailors led a revolt in the naval ports of Wilhelmshaven on 29 October 1918, followed by the Kiel mutiny in the first days of November. These disturbances spread the spirit of civil unrest across Germany and ultimately led to the proclamation of a republic on 9 November 1918. Shortly thereafter, Emperor Wilhelm II abdicated his throne and fled to the Netherlands.

In the wake of the mutiny Bolshevik-style workers' councils were established across Germany, with socialist ideals reigning dominant among the revolutionaries. However, the councils did not initially establish absolute power, because the leadership of the main workers' party, the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), opposed their rule. Instead the SPD sought the creation of a parliamentary republic, cooperating with liberal and conservative parties, as well as the military. Despite the SPD's course, in areas where radical influences prevailed attempts were made to establish council republics. The radical current was led by the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD), which had been formed by anti-war SPD members in 1917. In some regions they had completely or largely usurped the position of the SPD as the most influential workers' party. In January 1919 part of the USPD's left-wing split off to form the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), joining with the Spartacus League and groups such as the Revolutionary Stewards. The two parties were able to capitalize on growing dissatisfaction among the working class with the SPD's policies, in which they had actively worked against the councils and striking workers.

The military became more and more wary of a potential socialist revolution throughout this period and made extensive efforts to try and root out unreliable elements. However, the army structure practically disintegrated with the end of the war, leaving the newly formed right-wing "Freikorps" as the only forces truly able to fight the revolutionaries. Many other soldiers were in fact sympathetic towards socialism and would go on to join the Spartacists. The tension between the monarchist-minded Freikorps and the republican-minded SPD government prompted a coup in April 1919. Though the Freikorps had been utilized by the government in multiple cases to combat revolutionary uprisings, they had come to believe they were being restrained from delivering a decisive blow. This, combined with frustration over a Polish uprising in the east and fear over the terms of a peace treaty with the Entente, created the conditions for the coup.

However, the coup proved to lay the conditions for a radicalization of the revolution. The SPD government fled from the seat of parliament in Weimar and refused to recognize the putschist government, while the unions called for a general strike. Council elections were organized in which the KPD and USPD were greatly strengthened, which led to the call for an uprising against the putschists, to be carried out on 1 May. The putschists, who had opted to install their own government following the SPD's refusal to negotiate, did not surrender power despite the ultimatum. However, following the escalation into a full blown civil war, as well as threats of invasion from the Entente, they opted to return power to the SPD, in hopes that they could use their influence to avert a socialist revolution. This was done under the controversial condition that the Freikorps would not punished, nor would it be restricted in crushing the rebellious workers.

By this point it was too late for the SPD to reverse the situation, as fierce fighting had already erupted between the Freikorps and workers' militias across the nation, while the party had suffered an internal crisis. Their inability to secure the surrender of the councils resulted in another coup in December 1919, in which a more stable military regime under General Kurt von Schleicher would lead a grand but ill fated offensive against the Spartacists, but not before publicly agreeing to humiliating peace terms with the Entente. After a climactic battle in Berlin, the counterrevolutionary Whites were driven into a full retreat. As the Spartacists neared absolute victory the French intervened in October 1920 to establish a buffer zone in Southern Germany, which they partially succeeded in doing. Following an armistice and peace terms the civil war ended with a Spartacist victory in November, but at the expense of lands in the west.

SPD and the World War

In the decade after 1900, the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) was the leading force in Germany's labour movement. With 35% of the national votes and 110 seats in the Reichstag elected in 1912, the Social Democrats had grown into the largest political party in Germany. Party membership was around one million, and the party newspaper (Vorwärts) attracted 1.5 million subscribers. The trade unions had 2.5 million members, most of whom probably supported the Social Democrats. In addition, there were numerous co-operative societies (for example, apartment co-ops, shop co-ops, etc.), and other organizations directly linked to the SPD and the labor unions, or else adhering to Social Democratic ideology.

At the European congresses of the second Socialist International, the SPD had always agreed to resolutions asking for combined action of Socialists in case of a war. Following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, the SPD, like other socialist parties in Europe, organised anti-war demonstrations during the July Crisis. After Rosa Luxemburg called for disobedience and rejection of war in the name of the entire party as a representative of the left wing of the party, the Imperial government planned to arrest the party leaders immediately at the onset of war. Friedrich Ebert, one of the two party leaders since 1913, travelled to Zürich with Otto Braun to save the party's funds from being confiscated.

After Germany declared war on the Russian Empire on 1 August 1914, the majority of the SPD newspapers shared the general enthusiasm for the war (the "Spirit of 1914"), particularly because they viewed the Russian Empire as the most reactionary and anti-socialist power in Europe. In the first days of August, the editors believed themselves to be in line with the late August Bebel, who had died the previous year. In 1904, he declared in the Reichstag that the SPD would support an armed defence of Germany against a foreign attack. In 1907, at a party convention in Essen, he even promised that he himself would "shoulder the gun" if it was to fight against Russia, the "enemy of all culture and all the suppressed". In the face of the general enthusiasm for the war among the population, which foresaw an attack by the Entente powers, many SPD deputies worried they might lose many of their voters with their consistent pacifism. In addition, the government of Imperial Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg threatened to outlaw all parties in case of war. On the other hand, the chancellor exploited the anti-Russian stance of the SPD to procure the party's approval for the war.

The party leadership and the party's deputies were split on the issue of support for the war: 96 deputies, including Friedrich Ebert, approved the war bonds demanded by the Imperial government. There were 14 deputies, headed by the second party leader, Hugo Haase, who spoke out against the bonds, but nevertheless followed party voting instructions and raised their hands in favour.

Thus, the entire SPD faction in the Reichstag voted in favour of the war bonds on 4 August 1914. It was with those decisions by the party and the unions that the full mobilisation of the German Army became possible. Haase explained the decision against his will with the words: "We will not let the fatherland alone in the hour of need!" The Emperor welcomed the so-called "truce" (Burgfrieden), declaring: "Ich kenne keine Parteien mehr, ich kenne nur noch Deutsche!" ("I no longer see parties, I see only Germans!").

Even Karl Liebknecht, who became one of the most outspoken opponents of the war, initially followed the line of the party that his father, Wilhelm Liebknecht, had cofounded: he abstained from voting and did not defy his own political colleagues. However, a few days later he joined the Gruppe Internationale (Group International) that Rosa Luxemburg had founded on 5 August 1914 with Franz Mehring, Wilhelm Pieck, and four others from the left wing of the party, which adhered to the prewar resolutions of the SPD. From that group emerged the Spartacus League (Spartakusbund) on 1 January 1916.

On 2 December 1914, Liebknecht voted against further war bonds, the only deputy of any party in the Reichstag to do so. Although he was not permitted to speak in the Reichstag to explain his vote, what he had planned to say was made public through the circulation of a leaflet that was claimed to be unlawful:

The present war was not willed by any of the nations participating in it and it is not waged in the interest of the Germans or any other people. It is an imperialist war, a war for capitalist control of the world market, for the political domination of huge territories and to give scope to industrial and banking capital.

Because of high demand, this leaflet was soon printed and evolved into the so-called "Political Letters" (German: Politische Briefe), collections of which were later published in defiance of the censorship laws under the name "Spartacus Letters" (Spartakusbriefe). As of December 1916, these were replaced by the journal Spartakus, which appeared irregularly until November 1918.

This open opposition against the party line put Liebknecht at odds with some party members around Haase who were against the war bonds themselves. In February 1915, at the instigation of the SPD party leadership, Liebknecht was conscripted for military service to dispose of him, the only SPD deputy to be so treated. Because of his attempts to organise objectors against the war, he was expelled from the SPD, and in June 1916, he was sentenced on a charge of high treason to four years in prison. While Liebknecht was in the army, Rosa Luxemburg wrote most of the "Spartacus Letters". After serving a prison sentence, she was put back in jail under "preventive detention" until the war ended.

The SPD Split

As the war dragged on and the death tolls rose, more SPD members began to question the adherence to the Burgfrieden (the truce in domestic politics) of 1914. The SPD also objected to the domestic misery that followed the dismissal of Erich von Falkenhayn as Chief of the General Staff in 1916. His replacement, Paul von Hindenburg, introduced the Hindenburg Programme by which the guidelines of German policy were de facto set by the Supreme Army Command (German: Oberste Heeresleitung), not the emperor and the chancellor. Hindenburg's subordinate, Erich Ludendorff, took on broad responsibilities for directing wartime policies that were extensive. Although the Emperor and Hindenburg were his nominal superiors, it was Ludendorff who made the important decisions. Hindenburg and Ludendorff persisted with ruthless strategies aimed at achieving military victory, pursued expansionist and aggressive war goals and subjugated civilian life to the needs of the war and the war economy. For the labour force, that often meant 12-hour work days at minimal wages with inadequate food. The Hilfsdienstgesetz (Auxiliary Service Law) forced all men not in the armed forces to work.

After the outbreak of the Russian February Revolution in 1917, the first organised strikes erupted in German armament factories in March and April, with about 300,000 workers going on strike. The strike was organized by a group called the Revolutionary Stewards (Revolutionäre Obleute), led by their spokesman Richard Müller. The group emerged from a network of left-wing unionists who disagreed with the support of the war that came from the union leadership. The American entry into World War I on 6 April 1917 threatened further deterioration in Germany's military position. Hindenburg and Ludendorff had called for an end to the moratorium on attacks on neutral shipping in the Atlantic, which had been imposed when the Lusitania, a British ship carrying US citizens, was sunk off Ireland in 1915. Their decision signaled a new strategy to stop the flow of US materiel to France to make a German victory (or at least a peace settlement on German terms) possible before the United States entered the war as a combatant. The emperor tried to appease the population in his Easter address of 7 April by promising democratic elections in Prussia after the war, but lack of progress in bringing the war to a satisfactory end dulled its effect. Opposition to the war among munitions workers continued to rise, and what had been a united front in favour of the war split into two sharply divided groups.

After the SPD leadership, under Friedrich Ebert, excluded the opponents of the war from his party, the Spartacists joined with so-called "Revisionists" such as Eduard Bernstein and Centrists such as Karl Kautsky to found the fully anti-war Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD) under the leadership of Hugo Haase on 9 April 1917. The SPD was now known as the Majority Social Democratic Party of Germany (MSPD) and continued to be led by Friedrich Ebert. The USPD demanded an immediate end to the war and a further democratisation of Germany but did not have a unified agenda for social policies. The Spartacist League, which until then had opposed a split of the party, now made up the left wing of the USPD. Both the USPD and the Spartacists continued their anti-war propaganda in factories, especially in the armament plants.

Seeking Peace

Leftist and rightist approaches

In spite of the optimism created by the surrender of Russia early in 1918, there could be no question that the military situation on the Western Front had become more precarious for the Germans after the United States entered the war in April 1917. In the wake of the United States declaration of war, the SPD in the Reichstag joined the "Interfactional Committee" with the Centre Party and the Progressive People's Party. In summer 1917, these three parties passed a peace resolution providing for a peace through rapprochement without annexations and payments, as opposed to a peace through victory and annexations, as the political right was demanding. Along with almost everyone else in the country, the committee still believed in victory. The Imperial German Supreme Army Command did not like this resolution, and in the negotiations from December 1917 to March 1918 with Russia, it imposed a harsh peace by victory.

The Supreme Command also rejected outright the "Fourteen Points" set out by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson on 8 January 1918. Wilson wanted peace on the basis of "self-determination of peoples" without victors or conquered. Hindenburg and Ludendorff rejected the offer because they believed themselves to be in a stronger position than they were before their victory over Russia. They continued to bet on a "peace through victory", with far-reaching annexations at the expense of Germany's enemies.

Request for ceasefire and change of constitution

After the victory in the east, the Supreme Army Command on 21 March 1918 launched its so-called Spring Offensive in the west to turn the war decisively in Germany's favour, but by July 1918, their last reserves were used up, and Germany's military defeat became certain. The Entente forces scored numerous successive victories in the Hundred Days Offensive between August and November 1918 that yielded huge territorial gains at the expense of Germany. The arrival of large numbers of fresh troops from the United States was a decisive factor.

In mid-September, the Balkan collapsed. The Kingdom of Bulgaria, an ally of the German Empire and Austria-Hungary, capitulated on 27 September. The political collapse of Austria-Hungary itself was now only a matter of days away.

On 29 September, the Supreme Army Command, at army headquarters in Spa, Belgium, informed Emperor Wilhelm II and the Imperial Chancellor Count Georg von Hertling, that the military situation was hopeless. Ludendorff said that he could not guarantee to hold the front for another 24 hours and demanded a request to the Entente powers for an immediate ceasefire. In addition, he recommended the acceptance of the main demand of Wilson to put the Imperial Government on a democratic footing in hopes of more favourable peace terms. This enabled him to protect the reputation of the Imperial Army and put the responsibility for the capitulation and its consequences squarely at the feet of the democratic parties and the Reichstag.

As he said to his staff officers on 1 October: "They now must lie on the bed that they have made us."

Thus, the so-called "stab-in-the-back legend" (German: Dolchstoßlegende) was born, according to which the revolutionaries had attacked the undefeated army from the rear and turned an almost-certain victory into a defeat.

In fact, the Imperial Government and the German Army shirked their responsibility for defeat from the very beginning and tried to place the blame for it on the new democratic government. The motivation behind it is verified by the following citation in the autobiography of Wilhelm Groener, Ludendorff's successor:

It was just fine with me when Army and Army Command remained as guiltless as possible in these wretched truce negotiations, from which nothing good could be expected.

In nationalist circles, the myth fell on fertile ground. The nationalists soon defamed the revolutionaries (and even politicians like Ebert who never wanted a revolution and did everything to prevent it) as "November Criminals" (Novemberverbrecher).

Although shocked by Ludendorff's report and the news of the defeat, the majority parties in the Reichstag, especially the SPD, were willing to take on the responsibility of government at the eleventh hour. As a convinced royalist, Hertling objected to handing over the reins to the Reichstag, thus Emperor Wilhelm II appointed Prince Maximilian von Baden as the new Imperial Chancellor on 3 October. The prince was considered a liberal, but at the same time a representative of the royal family. In his cabinet, Social Democrats dominated. The most prominent and highest-ranking one was Philipp Scheidemann, as under-secretary without portfolio. The following day, the new government offered to the Allies the truce that Ludendorff had demanded.

It was only on 5 October that the German public was informed of the dismal situation that it faced. In the general state of shock about the defeat, which now had become obvious, the constitutional changes, formally decided by the Reichstag on 28 October, went almost unnoticed. From then on, the Imperial Chancellor and his ministers depended on the confidence of the parliamentary majority. After the Supreme Command had passed from the emperor to the Imperial Government, the German Empire changed from a constitutional to a parliamentary monarchy. As far as the Social Democrats were concerned, the so-called October Constitution met all the important constitutional objectives of the party. Ebert already regarded 5 October as the birthday of German democracy since the emperor voluntarily ceded power and so he considered a revolution unnecessary.

Third Wilson note and Ludendorff's dismissal

In the following three weeks, American President Woodrow Wilson responded to the request for a truce with three diplomatic notes. As a precondition for negotiations, he demanded the retreat of Germany from all occupied territories, the cessation of submarine activities and (implicitly) the emperor's abdication. This last demand was intended to render the process of democratisation irreversible.

After the third note of 24 October, General Ludendorff changed his mind and declared the conditions of the Allies to be unacceptable. He now demanded the resumption of the war that he had declared lost only one month earlier. While the request for a truce was being processed, the Allies came to realise Germany's military weakness. The German troops had come to expect the war to end and were anxious to return home. They were scarcely willing to fight more battles, and desertions were increasing.

For the time being, the Imperial government stayed on course and replaced Ludendorff as First General Quartermaster with General Groener. Ludendorff fled with false papers to neutral Sweden. On 5 November, the Entente Powers agreed to take up negotiations for a truce, but after the third note, many soldiers and the general population believed that the emperor had to abdicate to achieve peace.

Revolution

Kiel Mutiny

While the war-weary troops and general population of Germany awaited the speedy end of the war, the Imperial Naval Command in Kiel under Admiral Franz von Hipper and Admiral Reinhard Scheer planned to dispatch the Imperial Fleet for a last battle against the Royal Navy in the southern North Sea. The two admirals sought to lead this military action on their own initiative, without authorization.

The naval order of 24 October 1918 and the preparations to sail triggered a mutiny among the affected sailors. The revolt soon precipitated a general revolution in Germany that would sweep aside the monarchy within a few days. The mutinous sailors had no intention of risking their lives so close to the end of the war. They were also convinced that the credibility of the new democratic government, engaged as it was in seeking an armistice with the victorious Entente, would have been compromised by a naval attack at such a crucial point in negotiations.

The sailors' revolt started in the Schillig Roads off Wilhelmshaven, where the German fleet had anchored in expectation of battle. During the night of 29–30 October 1918, some crews refused to obey orders. Sailors on board three ships of the Third Navy Squadron refused to weigh anchor. Part of the crew of SMS Thüringen and SMS Helgoland, two battleships of the I Battle Squadron, committed outright mutiny and sabotage. However, when some torpedo boats directed their guns onto these ships a day later, the mutineers gave up and were led away without any resistance. Nonetheless, the Naval Command had to drop its plans for a naval engagement with British naval forces since it was felt that the loyalty of the crews could not be relied upon any more. The III Battle Squadron was ordered back to Kiel.

The squadron commander Vice-Admiral Kraft carried out a maneuver with his battleships in Heligoland Bight. The maneuver was successful, and he believed that he had regained control of his crews. While moving through the Kiel Canal, he had 47 of the crew of SMS Markgraf, who were seen as the ringleaders, imprisoned. In Holtenau (the end of the canal in Kiel), they were taken to the Arrestanstalt (military prison) in Kiel and to Fort Herwarth in the north of Kiel.

The sailors and stokers were now pulling out all the stops to prevent the fleet setting sail again and to achieve the release of their comrades. Some 250 met in the evening of 1 November in the Union House in Kiel. Delegations sent to their officers requesting the mutineers' release were not heard. The sailors were now looking for closer ties to the unions, the USPD and the SPD. Then, the Union House was closed by police, leading to an even larger joint open air meeting on 2 November. Led by the sailor Karl Artelt, who worked in the torpedo workshop in Kiel-Friedrichsort, and by the mobilised shipyard worker Lothar Popp, both USPD members, the sailors called for a mass meeting the following day at the same place: the Großer Exerzierplatz (large drill ground).

This call was heeded by several thousand people on the afternoon of 3 November, with workers' representatives also present. The slogan "Peace and Bread" (Frieden und Brot) was raised, showing that the sailors and workers demanded not only the release of the prisoners but also the end of the war and the improvement of food provisions. Eventually, the people supported Artelt's call to free the prisoners, and they moved towards the military prison. Sub-Lieutenant Steinhäuser, in order to stop the demonstrators, ordered his patrol to fire warning shots and then to shoot directly into the demonstration; 7 people were killed and 29 severely injured. Some demonstrators also opened fire. Steinhäuser himself was seriously injured by rifle-butt blows and shots, but contrary to later statements, he was not killed. After this eruption, the demonstrators and the patrol dispersed. Nevertheless, the mass protest turned into a general revolt.

On the morning of 4 November, groups of mutineers moved through the town of Kiel. Sailors in a large barracks compound in a northern district mutinied: after a divisional inspection by the commander, spontaneous demonstrations took place. Artelt organised the first soldiers' council and soon many more were set up. The governor of the naval station, Wilhelm Souchon, was compelled to negotiate.

The imprisoned sailors and stokers were freed, and soldiers and workers brought public and military institutions under their control. In breach of Souchon's promise, separate troops advanced to end the rebellion but were intercepted by the mutineers and sent back or decided to join the sailors and workers. By the evening of 4 November, Kiel was firmly in the hands of about 40,000 rebellious sailors, soldiers and workers, as was Wilhelmshaven two days later.

On the same evening, the SPD deputy Gustav Noske arrived in Kiel and was welcomed enthusiastically, but he had orders from the new government and the SPD leadership to bring the uprising under control. He had himself elected chairman of the soldiers' council and reinstated peace and order. Some days later he took over the governor's post, and Lothar Popp of the USPD became chairman of the overall soldiers' council.

During the following weeks, Noske succeeded in reducing the influence of the councils in Kiel, but he could not prevent the spread of the revolution throughout Germany. The events had already spread far beyond Kiel.

Spread of revolution to the entire German Empire

Around 4 November, delegations of the sailors dispersed to all of the major cities in Germany. By 7 November, the revolution had seized all large coastal cities as well as Hanover, Brunswick, Frankfurt on Main, and Munich. In Munich, a "Workers' and Soldiers' Council" forced the last King of Bavaria, Ludwig III, to abdicate. Bavaria was the first member state of the German Empire to be declared a Volksstaat, the People's State of Bavaria, by Kurt Eisner of the USPD. In the following days, the dynastic rulers of all the other German states abdicated; the last was Günther Victor, Prince of Schwarzburg, on 23 November.

The Workers' and Soldiers' Councils were almost entirely made up of MSPD and USPD members. Their program was democracy, pacifism and anti-militarism. Apart from the dynastic families, they deprived only the military commands of their power and privilege. The duties of the imperial civilian administration and office bearers such as police, municipal administrations and courts were not curtailed or interfered with. There were hardly any confiscations of property or occupation of factories, because such measures were expected from the new government. In order to create an executive committed to the revolution and to the future of the new government, the councils for the moment claimed only to take over the supervision of the administration from the military commands.

Thus, the MSPD was able to establish a firm base on the local level. But while the councils believed they were acting in the interest of the new order, the party leaders of the MSPD regarded them as disturbing elements for a peaceful changeover of power that they imagined already to have taken place. Along with the middle-class parties, they demanded speedy elections for a national assembly that would make the final decision on the constitution of the new state. This soon brought the MSPD into opposition with many of the revolutionaries. It was especially the USPD that took over their demands, one of which was to delay elections as long as possible to try to achieve a fait accompli that met the expectations of a large part of the workforce.

Notably, revolutionary sentiment did not affect the eastern lands of the Empire to any considerable extent, apart from isolated instances of agitation in Breslau and Königsberg. But interethnic discontent among Germans and minority Poles in the eastern extremities of Silesia, long suppressed in Wilhelmine Germany, would eventually lead to the Silesian Uprisings.

By the time the revolution was over in 1918, all 21 German monarchs had been dethroned.

Reactions in Berlin

Ebert agreed with Prince Maximilian that a social revolution must be prevented and that state order must be upheld at all costs. In the restructuring of the state, Ebert wanted to win over the middle-class parties that had already cooperated with the SPD in the Reichstag in 1917, as well as the old elites of the German Empire. He wanted to avoid the spectre of radicalisation of the revolution along Russian lines and he also worried that the precarious supply situation could collapse, leading to the takeover of the administration by inexperienced revolutionaries. He was certain that the SPD would be able to implement its reform plans in the future due to its parliamentary majorities.

Ebert did his best to act in agreement with the old powers and intended to save the monarchy. In order to demonstrate some success to his followers, he demanded the abdication of the emperor as of 6 November. But Wilhelm II, still in his headquarters in Spa, was playing for time. After the Entente had agreed to truce negotiations on that day, he hoped to return to Germany at the head of the army and to quell the revolution by force.

According to notes taken by Prince Maximilian, Ebert declared on 7 November, "If the Kaiser does not abdicate, the social revolution is unavoidable. But I do not want it, indeed I hate it like sin." (Wenn der Kaiser nicht abdankt, dann ist die soziale Revolution unvermeidlich. Ich aber will sie nicht, ja, ich hasse sie wie die Sünde.) The chancellor planned to travel to Spa and convince the emperor personally of the necessity to abdicate. But this plan was overtaken by the rapidly deteriorating situation in Berlin.

Saturday, 9 November 1918: two proclamations of a republic

In order to remain master of the situation, Friedrich Ebert demanded the chancellorship for himself on the afternoon of 9 November, the day of the emperor's abdication.

The news of the abdication came too late to make any impression on the demonstrators. Nobody heeded the public appeals. More and more demonstrators demanded the total abolition of the monarchy. Karl Liebknecht, just released from prison, had returned to Berlin and re-founded the Spartacist League the previous day. At lunch in the Reichstag, the SPD deputy chairman Philipp Scheidemann learned that Liebknecht planned the proclamation of a socialist republic. Scheidemann did not want to leave the initiative to the Spartacists and without further ado, he stepped out onto a balcony of the Reichstag. From there, he proclaimed a republic before a mass of demonstrating people on his own authority (against Ebert's expressed will). A few hours later, the Berlin newspapers reported that in the Berlin Lustgarten – at probably around the same time — Liebknecht had proclaimed a socialist republic, which he affirmed from a balcony of the Berlin City Palace to an assembled crowd at around 4 pm.

At that time, Karl Liebknecht's intentions were little known to the public. The Spartacist League's demands of 7 October for a far-reaching restructuring of the economy, the army and the judiciary – among other things by abolishing the death penalty — had not yet been published. The biggest bone of contention with the SPD was to be the Spartacists' demand for the establishment of "unalterable political facts" on the ground by social and other measures before the election of a constituent assembly, while the SPD wanted to leave the decision on the future economic system to the assembly.

Ebert was faced with a dilemma. The first proclamation he had issued on 9 November was addressed "to the citizens of Germany".

Ebert wanted to take the sting out of the revolutionary mood and to meet the demands of the demonstrators for the unity of the labour parties. He offered the USPD participation in the government and was ready to accept Liebknecht as a minister. Liebknecht in turn demanded the control of the workers' councils over the army. As USPD chairman Hugo Haase was in Kiel the deliberations went on. The USPD deputies were unable to reach a decision that day.

Neither the early announcement of the emperor's abdication, Ebert's assumption of the chancellorship, nor Scheidemann's proclamation of the republic were covered by the constitution. These were all revolutionary actions by protagonists who did not want a revolution, but nevertheless took action. However, a real revolutionary action took place the same evening that would later prove to have been in vain.

Around 8 pm, a group of 100 Revolutionary Stewards from the larger Berlin factories occupied the Reichstag. Led by their spokesmen Richard Müller and Emil Barth, they formed a revolutionary parliament. Most of the participating stewards had already been leaders during the strikes earlier in the year. They did not trust the SPD leadership and had planned a coup for 11 November independently of the sailors' revolt, but were surprised by the revolutionary events since Kiel. In order to snatch the initiative from Ebert, they now decided to announce elections for the following day. On that Sunday, every Berlin factory and every regiment was to elect workers' and soldiers' councils that were then in turn to elect a revolutionary government from members of the two labour parties (SPD and USPD). This Council of the People's Deputies (Rat der Volksbeauftragten) was to execute the resolutions of the revolutionary parliament as the revolutionaries intended to replace Ebert's function as chancellor and president.

Sunday, 10 November: revolutionary councils elected, Armistice

The same evening, the SPD leadership heard of these plans. As the elections and the councils' meeting could not be prevented, Ebert sent speakers to all Berlin regiments and into the factories in the same night and early the following morning. They were to influence the elections in his favour and announce the intended participation of the USPD in the government.

In turn, these activities did not escape the attention of Richard Müller and the revolutionary shop stewards. Seeing that Ebert would also be running the new government, they planned to propose to the assembly not only the election of a government, but also the appointment of an Action Committee. This committee was to co-ordinate the activities of the Workers' and Soldiers' Councils. For this election, the Stewards had already prepared a list of names on which the SPD was not represented. In this manner, they hoped to install a monitoring body acceptable to them watching the government.

In the assembly that convened on 10 November in the Circus Busch, the majority stood on the side of the SPD: almost all Soldiers' Councils and a large part of the workers representatives. They repeated the demand for the "Unity of the Working Class" that had been put forward by the revolutionaries the previous day and now used this motto in order to push through Ebert's line. As planned, three members of each socialist party were elected into the "Council of People's Representatives": from the USPD, their chairman Hugo Haase, Georg Ledebour and Emil Barth for the Revolutionary Stewards; from the SPD Ebert, Scheidemann and the Magdeburg deputy Otto Landsberg.

The proposal by the shop stewards to elect an action committee additionally took the SPD leadership by surprise and started heated debates. Ebert finally succeeded in having this 24-member "Executive Council of Workers' and Soldiers' Councils" equally filled with SPD and USPD members. The Executive Council was chaired by Richard Müller and Brutus Molkenbuhr.

On the evening of 10 November, there was a phone call between Ebert and General Wilhelm Groener, the new First General Quartermaster in Spa, Belgium. Assuring Ebert of the support of the army, the general was given Ebert's promise to reinstate the military hierarchy and, with the help of the army, to take action against the councils.

In the turmoil of this day, the Ebert government's acceptance of the harsh terms of the Entente for a truce, after a renewed demand by the Supreme Command, went almost unnoticed. On 11 November, the Centre Party deputy Matthias Erzberger, on behalf of Berlin, signed the armistice agreement in Compiègne, France, and the Great War came to an end.

Double rule

Although Ebert had saved the decisive role of the SPD, he was not happy with the results. He did not regard the Council Parliament and the Executive Council as helpful, but only as obstacles impeding a smooth transition from empire to a new system of government. The whole SPD leadership mistrusted the councils rather than the old elites in army and administration, and they considerably overestimated the old elite's loyalty to the new republic. What troubled Ebert most was that he could not now act as chancellor in front of the councils, but only as chairman of a revolutionary government. Though he had taken the lead of the revolution only to halt it, conservatives saw him as a traitor.

In theory, the Executive Council was the highest-ranking council of the revolutionary regime and therefore Müller the head of state of the new declared "Socialist Republic of Germany". But in practice, the council's initiative was blocked by internal power struggles. The Executive Council decided to summon an "Imperial Council Convention" in December to Berlin. In the eight weeks of double rule of councils and imperial government, the latter always was dominant. Although Haase was officially a chairman in the Council with equal rights, the whole higher level administration reported only to Ebert.

The SPD worried that the revolution would end in a Council (Soviet) Republic, following the Russian example. However, the secret Ebert-Groener pact did not win over the Imperial Officer Corps for the republic. As Ebert's behaviour became increasingly puzzling to the revolutionary workers, the soldiers and their stewards, the SPD leadership lost more and more of their supporters' confidence, without gaining any sympathies from the opponents of the revolution on the right.

Stinnes–Legien Agreement

The revolutionaries disagreed among themselves about the future economic and political system. Both SPD and USPD favoured placing at least heavy industry under democratic control. The left wings of both parties and the Revolutionary Stewards wanted to go beyond that and establish a "direct democracy" in the production sector, with elected delegates controlling the political power. It was not only in the interest of the SPD to prevent a Council Democracy; even the unions would have been rendered superfluous by the councils.

To prevent this development, the union leaders under Carl Legien and the representatives of big industry under Hugo Stinnes and Carl Friedrich von Siemens met in Berlin from 9 to 12 November. On 15 November, they signed an agreement with advantages for both sides: the union representatives promised to guarantee orderly production, to end wildcat strikes, to drive back the influence of the councils and to prevent a nationalisation of means of production. For their part, the employers guaranteed to introduce the eight-hour day, which the workers had demanded in vain for years. The employers agreed to the union claim of sole representation and to the lasting recognition of the unions instead of the councils. Both parties formed a "Central Committee for the Maintenance of the Economy" (Zentralausschuss für die Aufrechterhaltung der Wirtschaft).

An "Arbitration Committee" (Schlichtungsausschuss) was to mediate future conflicts between employers and unions. From now on, committees together with the management were to monitor the wage settlements in every factory with more than 50 employees.

With this arrangement, the unions had achieved one of their longtime demands, but undermined all efforts for nationalising means of production and largely eliminated the councils.

Interim government and council movement

The Reichstag had not been summoned since 9 November. The Council of the People's Deputies and the Executive Council had replaced the old government, but the previous administrative machinery remained unchanged. Imperial servants had only representatives of SPD and USPD assigned to them. These servants all kept their positions and continued to do their work in most respects unchanged.

On 12 November, the Council of People's Representatives published its democratic and social government programme. It lifted the state of siege and censorship, abolished the "Gesindeordnung" ("servant rules" that governed relations between servant and master) and introduced universal suffrage from 20 years up, for the first time for women. There was an amnesty for all political prisoners. Regulations for the freedom of association, assembly and press were enacted. The eight-hour day became statutory on the basis of the Stinnes–Legien Agreement, and benefits for unemployment, social insurance, and workers' compensation were expanded.

At the insistence of USPD representatives, the Council of People's Representatives appointed a "Nationalisation Committee" including Karl Kautsky, Rudolf Hilferding and Otto Hue, among others. This committee was to examine which industries were "fit" for nationalisation and to prepare the nationalisation of the coal and steel industry. It sat until 7 April 1919, without any tangible result. "Self-Administration Bodies" were installed only in coal and potash mining and in the steel industry. From these bodies emerged the modern German Works or Factory Committees. Socialist expropriations were not initiated.

The SPD leadership worked with the old administration rather than with the new Workers' and Soldiers' Councils, because it considered them incapable of properly supplying the needs of the population. As of mid-November, this caused continuing strife with the Executive Council. As the Council continuously changed its position following whoever it just happened to represent, Ebert withdrew more and more responsibilities planning to end the "meddling and interfering" of the Councils in Germany for good. But Ebert and the SPD leadership by far overestimated the power not only of the Council Movement but also of the Spartacist League. The Spartacist League, for example, never had control over the Council Movement as the conservatives and parts of the SPD believed.

In Leipzig, Hamburg, Bremen, Chemnitz, and Gotha, the Workers' and Soldiers' Councils took the city administrations under their control. In addition, in Brunswick, Düsseldorf, Mülheim/Ruhr, and Zwickau, all civil servants loyal to the emperor were arrested. In Hamburg and Bremen, "Red Guards" were formed that were to protect the revolution. The councils deposed the management of the Leuna works, a giant chemical factory near Merseburg. The new councils were often appointed spontaneously and arbitrarily and had no management experience whatsoever. But a majority of councils came to arrangements with the old administrations and saw to it that law and order were quickly restored. For example, Max Weber was part of the workers' council of Heidelberg, and was pleasantly surprised that most members were moderate German liberals. The councils took over the distribution of food, the police force, and the accommodation and provisions of the front-line soldiers that were gradually returning home.

Former imperial administrators and the councils depended on each other: the former had the knowledge and experience, the latter had political clout. In most cases, SPD members had been elected into the councils who regarded their job as an interim solution. For them, as well as for the majority of the German population in 1918–19, the introduction of a Council Republic was never an issue, but they were not even given a chance to think about it. Many wanted to support the new government and expected it to abolish militarism and the authoritarian state. Being weary of the war and hoping for a peaceful solution, they partially overestimated the revolutionary achievements.

General Council Convention

As decided by the Executive Committee, the Workers' and Soldiers' Councils in the whole empire sent deputies to Berlin, who were to convene on 16 December in the Circus Busch for the "First General Convention of Workers' and Soldiers' Councils" (Erster Allgemeiner Kongress der Arbeiter- und Soldatenräte). On 15 December, Ebert and General Groener had troops ordered to Berlin to prevent this convention and to regain control of the capital. On 16 December, one of the regiments intended for this plan advanced too early. In an attempt to arrest the Executive Council, the soldiers opened fire on a demonstration of unarmed "Red Guards", representatives of Soldiers' Councils affiliated with the Spartacists; 16 people were killed.

With this, the potential for violence and the danger of a coup from the right became visible. In response to the incident, Rosa Luxemburg demanded the peaceful disarmament of the homecoming military units by the Berlin workforce in the daily newspaper of the Spartacist League Red Flag (Rote Fahne) of 12 December. She wanted the Soldiers' Councils to be subordinated to the Revolutionary Parliament and the soldiers to become "re-educated".

On 10 December, Ebert welcomed ten divisions returning from the front hoping to use them against the councils. As it turned out, these troops also were not willing to go on fighting. The war was over, Christmas was at the door and most of the soldiers just wanted to go home to their families. Shortly after their arrival in Berlin, they dispersed. The blow against the Convention of Councils did not take place.

This blow would have been unnecessary anyway, because the convention that took up its work 16 December in the Prussian House of Representatives consisted mainly of SPD followers. Not even Karl Liebknecht had managed to get a seat. The Spartacist League was not granted any influence. On 19 December, the councils voted 344 to 98 against the creation of a council system as a basis for a new constitution. Instead, they supported the government's decision to call for elections for a constituent national assembly as soon as possible. This assembly was to decide upon the state system.

The convention disagreed with Ebert only on the issue of control of the army. The convention was demanding a say for the Central Council that it would elect, in the supreme command of the army, the free election of officers and the disciplinary powers for the Soldiers' Councils. That would have been contrary to the agreement between Ebert and General Groener. They both spared no effort to undo this decision. The Supreme Command (which in the meantime had moved from Spa to Kassel), began to raise loyal volunteer corps (the Freikorps) against the supposed Bolshevik menace. Unlike the revolutionary soldiers of November, these troops were monarchist-minded officers and men who feared the return into civil life.

Christmas crisis of 1918

After 9 November, the government ordered the newly created People's Navy Division (Volksmarinedivision) from Kiel to Berlin for its protection and stationed it in the Royal Stables (Neuer Marstell) across from the Berlin City Palace (Berlin Schloss or Berlin Stadtschloss). The division was considered absolutely loyal and had indeed refused to participate in the coup attempt of 6 December. The sailors even deposed their commander because they saw him as involved in the affair. It was this loyalty that now gave them the reputation of being in favor of the Spartacists. Ebert demanded their disbanding and Otto Wels, as of 9 November the Commander of Berlin and in line with Ebert, refused the sailors' pay.

The dispute escalated on 23 December. After having been put off for days, the sailors occupied the Imperial Chancellery itself, cut the phone lines, put the Council of People's Representatives under house arrest and captured Otto Wels. The sailors did not exploit the situation to eliminate the Ebert government, as would have been expected from Spartacist revolutionaries. Instead, they just insisted on their pay. Nevertheless, Ebert, who was in touch with the Supreme Command in Kassel via a secret phone line, gave orders to attack the Residence with troops loyal to the government on the morning of 24 December. The sailors repelled the attack under their commander Heinrich Dorrenbach, losing about 30 men and civilians in the fight. The government troops had to withdraw from the centre of Berlin. They themselves were now disbanded and integrated into the newly formed Freikorps. To make up for their humiliating withdrawal, they temporarily occupied the editor's offices of the Red Flag. But military power in Berlin once more was in the hands of the People's Navy Division. The sailors did not take advantage of the situation.

With the situation deteriorating, the representatives of the USPD in the revolutionary government threatened to withdraw. For Ebert this was a difficult prospect at a difficult time. The military command had increasingly lost its patience, and this left Ebert with the prospect of losing both political and military support. At the same time, Ledebour warned his comrades against withdrawing from the government, fearing it would leave the MSPD unchecked. After a series of heated meetings, the USPD representatives ultimately held their ground. As per a compromise between the MSPD and USPD, elections were scheduled for 16 February. This was eventually delayed to 23 February due to labour unrest in the Ruhr.

USPD Congress and the founding of the Communist Party

With the USPD having gained leverage over Ebert, the party soon looked internally. The revolutionary wing of the party had long wanted to hold a congress to determine the direction of the party. It was quickly organized between 12 and 16 January in order to establish a direction for the election campaign. The Spartacists present wielded great influence with the aid of veteran figures like Ledebour. The ultimate goals of Luxemburg, Jogiches and Liebknecht were largely unknown to most of the congress. They had been eagerly awaiting the moment to force a vote on the future of the party, which they hoped to use as a vessel to establish a new communist party that would usurp the USPD.

The vote was held on 14 January after the Revolutionary Stewards supported the efforts of the Spartacists. 344 delegates were present, and 245 voted in favor of decisively adopting a revolutionary platform in favor of council democracy. As expected, this produced great rifts with reformists like Haase. Failed negotiations were held between Haase and Liebknecht. However, the stage had already been set. On 16 January, the Spartacists and their allies split from the party and held their founding congress a day later. The demands of the Revolutionary Stewards were met and they crucially agreed to join the newly founded Communist Party of Germany (KPD). A majority of USPD members joined the KPD as part of the split.

One of the issues in the founding congress was over whether or not to participate in the upcoming elections. A number of ultra-left members from the IKD tried to prevent participation. However, the majority of the party, led by Luxemburg and Jogiches, agreed to participate, while also accepting that parliamentarism would never be the way of achieving socialism. Georg Ledebour supported the party but did not join it, rather seeking to work within the remnants of the USPD to maintain cordial relations with the KPD.

The KPD had only a little over a month to prepare for the elections. The prospects of achieving great success seemed low, but a major opportunity opened when large strikes erupted in the Ruhr in early February. The KPD emerged decisively as leaders of the strike action, which drew as much as 300,000 workers. The SPD had initially supported the strike action, but suddenly withdrew, leaving representatives of the KPD and USPD to approve the strike. The strike action ended only a few days before the election, with baffled workers flocking to the KPD and USPD in face of the SPD's support for the so-called "Freikorps", which had violently clashed with the strikers. Simultaneously the KPD established its influence over Berlin with the support of the Revolutionary Stewards and the Volksmarinedivision.

National Assembly election

Main Article: German federal election, 1919

On 23 February 1919, a Constituent National Assembly (Verfassungsgebende Nationalversammlung) was elected. Aside from SPD, KPD and USPD, the Catholic Centre Party took part, and so did several middle-class parties that had established themselves since November: the left-liberal German Democratic Party (DDP), the national-liberal German People's Party (DVP) and the conservative, nationalist German National People's Party (DNVP).

The chaos and division throughout the revolution left its mark on the results of the election. The SPD emerged on top, achieving 34.6% of the vote. They formed a coalition with DDP and Centre known as the Weimar Coalition, with the involved parties having collectively received 72.5% of the votes cast. The KPD achieved 4.4% of the vote, coming just slightly ahead of the DVP. Though far from what they had desired, the result was nonetheless surprising given how recently the KPD had been established. The USPD achieved 7% of the vote, bolstered in comparison to the KPD due to name recognition. Collectively this gave the revolutionary left 11.4% of the vote, a far cry from a majority, which the SPD used to its advantage. Also notable was the later election of 2 representatives on 3 March for German troops stationed in the East, in which right-leaning parties achieved only 1.4% of the vote, swamped by the SPD, USPD and KPD.

Interim

Governance of the Weimar Coalition

The parliament met for the first time on 12 March 1919, in the city of Weimar, Thuringia, as it was considered a politically peaceful location. Though the Weimar Coalition held a firm majority in parliament, the goals of the member parties were far from coherent. Each presented their own vision for a post-revolutionary Germany. At the same time the government came under great scrutiny from both the nationalist right, which had outright opposed the republic since its inception, and the revolutionary left, which favored a political system based around the workers' and soldiers' councils. Thus the government of the Weimar Coalition was given the impossible task of either appeasing the opposition while not destroying the coalition, or crushing the opposition without inciting a civil war.

At the same time the loyalty of the nascent Reichswehr to the government crumbled from two perspectives. On one hand, the predominantly right-wing military command had long grown dissatisfied with the government, with many prominent commanders internally seeking to undermine and even overthrow the republic. On the other hand the influence of the revolutionary socialists had grown within the ranks of the Reichswehr, and it became increasingly difficult to prevent a breakdown of order in the military or, even worse, mass defections to the revolutionaries. As demonstrated in December, the army could not be fully trusted to suppress revolutionary rebellions. Thus the military had to look towards the Freikorps to reliably crush the revolution, who were then supposed to form the core of the Reichswehr. This effort, however, was complicated by the election, which had to an extent legitimized the revolutionary socialists by giving them a place on the political stage. Thus no easy path was left for destroying the revolution in spite of the ambitions of the military command and their uneasy benefactors in the government.

April Putsch and council elections

Though the military command as a whole could not find a clear direction, some within their ranks did. The 1,500 strong Marinebrigade Ehrhardt, which had been ordered to move south to "maintain order" in Munich and had previously distinguished itself for crushing a revolt in Wilhelmshaven, instead turned upon the government in Weimar on 8 April. This coup, however, was not a spontaneous act as it initially appeared, but rather a planned action with numerous important benefactors such as the prominent generals Erich Ludendorff and Otto von Below, the Berlin area Freikorps commander Walther von Lüttwitz, Guards Cavalry Rifle Division commander Waldemar Pabst and his press chief Friedrich Grabowski, East Prussian Governor Adolf von Batocki-Friebe, and DNVP politicians Georg Schiele and Gottfried Traub, among others. Many of these figures had belonged to Wolfgang Kapp's wartime era German Fatherland Party, with Kapp himself taking a background role in the putsch preparations. Though he had no involvement in the coup preparations, SPD politician August Winnig supported it after it had began, while President Ebert's officer manager Rudolf Nadolny was inclined to do the same. Many Freikorps commanders were aware of the plan and those available were prepared to support it, having feared a loss of control over their formations after the planned restructuring of the Reichswehr in June. The publicized demands by the Entente for the deportation and prosecution of war criminals also played a significant factor, as did a general opposition to the anticipated disarmament. Additionally, the perpetrators of the putsch were part of a larger group advocating for a continuation of the war, with some figures like Batocki also advocating the so called "Oststaat-Plan", in which the German army would fight a continued war with the Entente and the Poles from a base of operations in Eastern Germany and the Baltics. Although the Prussian Minister of War Walther Reinhardt was a supporter of the Oststaat-Plan and an opponent to the planned downsizing of the army, he chose not to readily support the putsch, but also did not attempt to turn any forces against it.

The intentions of the putschists were not immediately clear. It was initially reported by the bourgeois press that military formations had moved into Weimar to defend against a "Spartacist rebellion". On 10 April the formation moved upon the Deutsches Nationaltheater, the seat of the National Assembly in Weimar. Ebert had phoned General Wilhelm Groener earlier in the day, confirming the Marinebrigade was out of the control of the high command, which had by this point relocated to Kolberg to direct operations against the Polish insurgents. Paul von Hindenburg, still the chief of the Supreme Army Command, was not involved in the coup preparations, in no small part because of a personal rivalry with Ludendorff, and he did not readily support it. When pressured by Groener to come out publicly against it, he instead opted to resign, and played no part in the coming civil war. Without any assured safety, the governing cabinet fled the city before the takeover of the Nationaltheater. The KPD and USPD representatives present in Weimar at the time too fled the city and took refuge in Saxony, and later Berlin. The other parliament members that remained were arrested, though many of the right-wing representatives sympathized with the coup and were quickly released. The putschists initially did not attempt to depose Ebert, but instead tried to court the president to their side. They demanded the dissolution of the National Assembly and the holding of new elections in which the KPD and USPD would be excluded, as well as unrestricted power in crushing the apparent "Spartacist menace". On the initiative of Pabst, who was in the process of leading the Guards Cavalry Rifle Division to secure Berlin, the putschists requested that Gustav Noske assume dictatorial powers. Noske had in fact known of the putsch preparations and had warned Pabst against it, but he had not shared this information with the rest of the government, nor had he taken any other steps to counter it. Although Noske sympathized with the ideals of the putschists, he refused to break with the SPD in fear of splitting the party.

Ebert's cabinet, now in exile in Brunswick, could not decisively decide on a course of action against the putschists. Chancellor Philip Scheidemann advocated immediate negotiations to avoid a perceived catastrophe, as did Gustav Bauer, but the establishment of an Ebert or Noske dictatorship was definitively ruled out. They did not wish to make any concessions that could be viewed as a total capitulation. Options to oppose the putschists were limited. Groener unsuccessfully tried to rally the military command to defend the Ebert government, but most of the command was sympathetic to the putschists and thus neutrality was the best that could be promised. Additionally, given the state of the army at the time and the fact the Freikorps constituted the only real coherent formations, there were no troops that could be organized to fight the putschists, and such a move would never have been authorized by the command even if it had been possible. Though there were many non-Freikorps barracked troops still mobilized and garrisoned across the country, they were not politically reliable and often held a closer allegiance to the councils. Opposite to Scheidemann and Bauer was SPD chair Otto Wels, who spoke out fervently against the putschists and advocated a general strike, a position also held by trade union chairman Carl Legien. However, Ebert feared that if such demonstrations began they could escalate to an uprising outside the control of the SPD. The call for a national general strike was initiated by the KPD and USPD on 12 April, which was met with support by a majority of workers' councils. The trade unions affiliated with the SPD supported the call that same day. The strike was already underway on 13 April when the Ebert government reluctantly agreed to support it.

The 13 April strike encompassed millions of workers across all of Germany. The move crippled the putschist government, which found itself unable to establish authority throughout the country. In numerous regions, particularly the Ruhr, Berlin and Saxony, armed workers arrested Freikorps detachments and security forces to prevent them from defecting to the putschist government. Many yet to be demobilized soldiers joined with the strike and the growing revolutionary militias. This was not a bloodless process, as in many cities and towns the Freikorps, security forces and local counterrevolutionary militias fought against the strikers and attempted to establish the rule of the putschist government, sometimes successfully. Simultaneously the unions called for a unity government to be formed between the SPD, USPD and KPD. This was a call vehemently opposed by Ebert and Scheidemann's cabinet, who especially viewed the communists with disdain, but the possibility of restoring the Weimar Coalition was soon brought into question after the Centre Party negotiated with the putschists and moved towards supporting it. By this point the putschists had accepted that they would not be able to bring Noske or Ebert to their side, so they set about forming their own cabinet on 14 April, with Kapp as chancellor. The KPD and USPD initiated a call for new council elections to be held, to "call upon the will of the proletariat", and while this was opposed by Ebert he was unable to prevent it, and the SPD councils did not oppose the move. To the left, this would constitute a decisive act of defiance against the putschists.

On 19 April a new Congress of Workers' and Soldiers' Councils was convened, with the combined KPD and USPD greatly increasing their representation compared to December 1918. The SPD was left as the largest singular party, but their representation was roughly equal to that of the revolutionaries, and they could no longer command a majority. Though the divided chamber was incapable of agreeing on every proposal, a general consensus was reached to call for violent resistance to the putschists as long as they continued to refuse to stand down, and they even issued a call for the "attainment of political power through the dictatorship of the proletariat". On the topic of a unity government no progress was reached, as the USPD and especially KPD delegates were highly skeptical of such a move, while the SPD delegates could not guarantee the Ebert government would agree. At the end of the congress a declaration was drafted, delivering a deadline for the putschists to surrender before 1 May, or else face the resistance of the working class. Meanwhile, the Freikorps formations, unable to maintain consistent contact with the putschist government and lacking definitive support from the high command, were unable to deliver the swift and decisive blow to the revolutionaries they had desired.

The Ebert government, still exiled in Brunswick, was also ironically paralyzed by the strike, as the situation had now rapidly grown out of their control. They were eager to leave the city considering the domineering revolutionary current among the local strikers, fearing they would be arrested by the revolutionary militia. The Weimar Coalition had, in fact, practically disintegrated. With no true authority over the army, the only armed elements that ostensibly stood on their side were the militias of the striking workers. Ebert continued to vehemently oppose any sort of unity government with the USPD and KPD, and did not deliver an endorsement for the call of an uprising against the putschists. In reality the militias were only tacitly aligned with his government anyway, with their primary goal being to uphold the victories gained in the revolution. Additionally, the SPD-aligned councils, trade unions, and even local party officials were no longer completely aligned with the government's agenda. With the putschist government remaining in power the perceived threat remained and the working class would now not stand down without the attainment of a socialist republic. Civil war had come, and Ebert could not stop it.

Civil War

May Uprising

Main article: May Uprising

As the putschist government had not yet stood down, the working class would join the call of the councils, rising in force on 1 May and striking out to defeat the Freikorps. Though 1 May is often portrayed in socialist historiography as the decisive day of the "second revolution", the civil war had already practically began weeks prior with the seizure of many regions by the workers' militias and the breakout of fighting with counterrevolutionary forces. The Freikorps was unable to individually beat down these armed movements due to the continued nationwide strike, and could do little to prevent an escalation on 1 May. Fearful of an inability to prevent another revolution, the putschist government made desperate efforts to moderate their stance, calling for a general election as soon as possible while offering additional concessions to the Ebert government. Their ambitious plans to continue the war against the Entente were never manifested, with the putschist cabinet even attempting to establish lines of communication with the Entente to usurp the Ebert government in negotiations. However, the Entente powers refused to recognize the putschists and maintained their contact with the Ebert government, which had repeatedly assured the Entente that order would be restored soon in order to avoid an invasion. Despite a growing current of defeatism among the supporters of the putsch, its principal leaders were still not seriously considering resigning. They were feeling more confident in wake of reports of various cities and towns being conquered by the Freikorps, though not all of these reports were true. In fact the strike movement was growing so militant in Thuringia that the location of the government in Weimar was becoming increasingly untenable, despite the recall of Freikorps forces to restore control in the region.

Though clashes had already been occurring in Berlin since the April Putsch, the mass organized uprising on 1 May would become known as the May Uprising, exalted in socialist historiography as the key rebellion of the May Revolution. It was notably crucial for securing the Berlin Executive Council as the national governing authority over the councils. The Volksmarinedivision, which had previously taken a passive stance in political affairs despite the revolutionary sympathies of its members, attempted to negotiate with the Freikorps elements present in the city to avert bloodshed. Met with hostility, they retreated, but one of their soldiers was fatally shot in the back by a Freikorps soldier. The enraged Volksmarinedivision now aligned itself solidly with the striking workers and set about distributing guns and aiding in organizing the militias. By now thousands of workers had armed themselves and were being organized haphazardly into an army. The primary Freikorps formation in the city, the Guards Cavalry Rifle Division, was unable to maintain their position in the city and withdrew to Potsdam after clashes with the Volksmarinedivision and the militia. By the end of the day the revolutionaries had seized control over Berlin and the immediate surrounding area, and the Berlin Executive Council now set about reforming itself as a rival government, leaving three governments ruling across Germany.

The uprising in Berlin did not necessarily mark the escalation to an outright civil war, but it is most often considered the beginning due to the creation of an organized socialist government directly opposing the authority of the putschists. The revolutionary strike escalated to uprisings throughout the country, with militias being established in many areas that had not yet escalated to armed opposition to the Freikorps. In other regions that had already been consolidated under the practical rule of the revolutionaries, such as the Ruhr, Thuringia and Saxony, the May Uprising initiated the formalization of military structures and organized offensives against the Freikorps. A very large portion of the militias were composed of workers with no combat experience, but they were also being bolstered by Great War veterans and defections of soldiers in active service. There was also a shortage of weapons and equipment in many areas and a lack of coherent structures to organize and direct these forces, in no small part because of an initial shortage of officers. The revolutionaries were in many locations able to improve their situation after seizing arms caches and capturing weapons from defeated Freikorps. At the same time, the more conservative and rural areas in Eastern Germany, which had not been active in the November Revolution and were actively embroiled in a counter-insurgency against Polish nationalists, experienced little unrest and acted as a stronghold for the putschists. Only in Silesia were significant revolutionary actions seen, particularly in Breslau and the heavily urbanized industrial and mining region in Upper Silesia. Despite these shortcomings, by the end of June the newly formed Berlin Government had control over most of Northern Germany, including the so-called "Red Belt" approximately spanning from Saxony to Thuringia to Berlin that had been a bastion of support for the KPD and USPD in the 1919 election. The Red Belt represented the center of the revolution, where the provisional socialist government exerted the strongest authority.

Capitulation of the putschists

On 5 May the putschist government, recognizing that the situation had now grown incredibly out of their control and that they could not exercise effective control over the nation, again entered contact with the Ebert government, which had by now moved to Stuttgart amidst the events, following guarantees from the local commanders. Kapp and the rest of the putschist government agreed to relinquish power, under the precondition they would not be arrested, and that the Freikorps would be unhindered in its continuance of the fight against the revolutionaries. Though the Ebert government had been made to swear not to negotiate with the putschists by the trade unions, accepting only an unconditional capitulation, they ultimately acceded to these demands the following day. Now they faced the task of halting the revolution and reestablishing their authority. An ultimatum was delivered to the workers' councils and the Berlin Executive Council, ordering them to cease fighting and disarm their forces. However, by this point there were already large scale battles occurring between the Freikorps and revolutionary militias. In response to the Ebert government, the Berlin Executive Council delivered their own terms, demanding the recognition of the workers' councils as the supreme authority in Germany, the formation of a unity government between the SPD, KPD and USPD, the removal of Defense Minister Gustav Noske, and the disbanding of the Freikorps as well as the arrest and prosecution of the putschists. Aware that the Freikorps represented the only hope to fight the revolution, the Ebert government broke off negotiations and prepared for war. Only in the case of Noske's removal were the demands met. Though some councils stood down, the majority did not, and by this point even the SPD-aligned unions would refuse to stand with Ebert and Scheidemann. Large scale shifts from the SPD to the USPD and KPD occurred within the councils, while those who did not were largely forced out. With this decision the formation of two rivalling governments, a counter-revolutionary one in Stuttgart and a revolutionary one in Berlin, was finalized, and radicals gained definitive control over the workers' councils and the workers loyal to them.

With the Ebert government restored, the negotiations with the Entente were able to be resumed in full. The National Assembly, now absent of most KPD and USPD parliamentarians, began to reconvene in Stuttgart. The German delegation was summoned to Versailles to receive the draft treaty, which was relayed to the government soon after. Though the government had just won a victory over the putschists, it now faced peace conditions widely viewed as harsh and unacceptable. Furthermore, the Entente, not yet fully aware of how far the situation had deteriorated, was unwilling to offer any concessions at first. While Scheidemann publicly spoke out against accepting the terms, the government could not help but face the reality that the army could not resist both the Spartacists and the Entente simultaneously. A continuation of the war was clearly impossible, a fact that the putschists had also been forced to accept. For the moment they could only hope for as long of a delay as possible in the delivering of the final treaty, after which an ultimatum would be delivered. It was feared that signing the treaty would undermine the critical support of the military, and above all it was feared that the unpopularity of the terms would drive the population into the arms of the Spartacists, who advocated peace without concessions. On the part of the Entente, as the gravity of the situation became more and more apparent a current of leniency began to emerge, particularly among the British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, who wished to avoid taking actions that could strengthen the Spartacists. He had already begun to lead a moderate current in the Paris Peace Conference before the April Putsch, but he now sought to use the revolutionary situation to bring the Americans and the French to his side. Most importantly, he advocated extending the deadline until Germany had stabilized.

Forming a German "red army"